In the spring of 2012, Spenser Johnson, a junior at Highland Park High School in Topeka, Kansas, was unpacking his acoustic bass before orchestra practice when a sign caught his eye. "Do you want to make money?" it asked.

The poster encouraged the predominantly poor students at Highland Park to enroll in a new, yearlong course that would provide lessons in basic economic principles and practical instruction on starting a business. Students would receive generous financial incentives including startup capital and scholarships after graduation. The course would begin that fall. Johnson eagerly signed up.

In some ways, the class looked like a typical high school business course, taught in a Highland Park classroom by a Highland Park teacher. But it was actually run by Youth Entrepreneurs, a nonprofit group created and funded primarily by Charles G. Koch, the billionaire chairman of Koch Industries.

The official mission of Youth Entrepreneurs is to provide kids with "business and entrepreneurial education and experiences that help them prosper and become contributing members of society." The underlying goal of the program, however, is to impart Koch's radical free-market ideology to teenagers. In the last school year, the class reached more than 1,000 students across Kansas and Missouri.

Lesson plans and class materials obtained by The Huffington Post make the course's message clear: The minimum wage hurts workers and slows economic growth. Low taxes and less regulation allow people to prosper. Public assistance harms the poor. Government, in short, is the enemy of liberty.

Though YE has avoided the public spotlight, the current structure of the program began to take shape in November 2009, documents show, when a team of associates at the Charles G. Koch Foundation launched an important project with Charles Koch's blessing: They would design and test what they called "a high school free market and liberty-based course" with support from members of the Koch family's vast nonprofit and political network. A pilot version of the class would be offered the following spring to students at the Wichita Collegiate School, an elite private prep school in Kansas where Koch was a top donor.

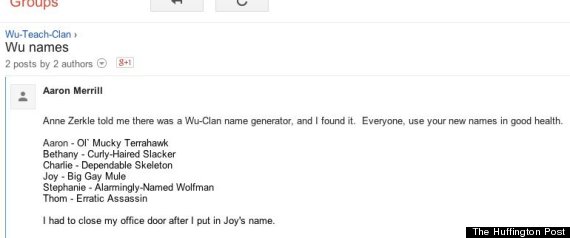

First, the Koch team chose its mascot: a golden eagle holding a knife in its beak. They also assigned each other nicknames: Ol' Mucky Terrahawk, Mighty Killer, Big Gay Mule, Midnight Bandit and Erratic Assassin. The group dubbed itself the "Wu-Teach Clan."

Over the next six months, members of the Wu-Teach Clan exchanged hundreds of emails with one another and with Koch lieutenants. They hashed out a strategy to infiltrate public schools after surveys showed that the wealthy prep school students largely failed to absorb their libertarian message. We know all this because the Wu-Teach Clan used a Google group that it had left open to the public.

The emails show that Charles Koch had a hands-on role in the design of the high school curriculum, directly reviewing the work of those responsible for setting up the course. The goal, the group said flatly, was to turn young people into "liberty-advancing agents" before they went to college, where they might learn "harmful" liberal ideas.

The Koch Foundation did not respond to requests for comment.

Charles Koch founded Youth Entrepreneurs in 1991 with his wife, Elizabeth Koch, who serves as chairman of the group's board. For much of the past two decades, YE offered little more than a pilot program teaching basic business skills -- and seemed an afterthought compared to the Kochs' massive investments in the political sphere. But the Kochs have renewed their focus on YE in recent years, pumping millions of dollars into it, expanding it considerably and molding it to project their worldview.

In 2007, YE reported assets of just over $450,000. In 2012, its assets topped $1.45 million. The lion's share of this growth was fueled by Koch family foundations.

During the 2012-2013 school year, YE's credit-bearing class reached more than 1,000 students in 29 schools in Kansas and Missouri, according to the group's annual report. Vernon Birmingham, YE's director of curriculum and teacher support, told HuffPost that the course will be in 42 schools in the coming school year. An offshoot in Atlanta, YE Georgia, reported being in 10 schools in the 2011-2012 school year. Since 2012, YE has also launched three major new initiatives: an online version of its course, an affiliate program to help rural schools access the class, and an after-school program, YE Academy, which served more than 500 students in its first year.

With spending on public education under heavy assault -- in large part by Koch-funded organizations and politicians they support -- the nation's poorest school districts are in desperate need of resources, making the free Koch curriculum an attractive alternative to nothing.

While the Kochs are perhaps best known for their support of conservative political candidates and causes, they have a longstanding interest in education. Charles and his brother David Koch were longtime supporters of the Libertarian Party before becoming Republican kingpins. David Koch won the party's nomination for vice president in 1980. That year, its platform proposed a drastic revision of the American education system: “We advocate the complete separation of education and state. Government schools lead to the indoctrination of children and interfere with the free choice of individuals. Government ownership, operation, regulation, and subsidy of schools and colleges should be ended.”

In recent years, through private charitable foundations, the Koch brothers have funneled tens of millions of dollars to colleges and universities -- most recently, a $25 million donation to the United Negro College Fund. They are also funding advocacy groups that are waging a widespread campaign to fight the Common Core State Standards, a set of benchmarks for public K-12 education adopted by most states. But YE is the most direct example of their growing imprint on American classrooms.

Koch-funded think tanks provide many of YE's course materials. Teachers are trained at Koch Industries headquarters and are required to read Charles Koch's book The Science of Success.

The focus on high school students is a key part of the Kochs' long-term effort to create a libertarian-minded society from the ground up.

"We hope to develop students' appreciation of liberty by improving free-market education," the Koch associates wrote during the program's initial planning stages. "Ultimately, we hope this will change the behavior of students who will apply these principles later on in life."

From the outset, the Koch associates identified the importance of recruiting teachers who would support the program's goals. "Relationships with teachers will be essential, as they will be the key conduits for getting the curriculum into the schools," they wrote in a December 2009 document describing their goals.

According to notes from a meeting with Koch associates in January 2010, executives from Koch-funded groups were concerned about how teachers might view the course. "What if teachers are unwilling? What incentives do teachers have?" associate Bethany Lowe wrote in an email, summarizing the discussion. "How will they not be scared of it?"

To find "liberty-minded" teachers who might be predisposed to help them, the team reached out to the network of libertarian groups that benefit from Koch family funding. Many of these groups, including the Institute for Humane Studies, the Bill of Rights Institute and the Market-Based Management Institute, host seminars and conferences specifically for teachers, and they were happy to help the team.

"Send me the language you want, I'll send it to our list!" wrote a marketing director at the Institute for Humane Studies in February 2010. A marketing employee at the Bill of Rights Institute said, "I would love to chat with you to help in any way possible with your project."

In addition, the Koch associates suggested looking for teachers who might be persuaded to teach the course. "Younger teachers might be more open to new ideas," Lowe wrote in the January 2010 meeting minutes. Lowe could not be reached for comment for this story.

Taylor Davis, the teacher in charge of the YE course at Highland Park High School, was one such Koch recruit. A first-year teacher at the time, Davis had received his public school education in affluent Olathe, Kansas. Motivated by a desire to teach inner-city kids, he earned two education degrees at the University of Kansas before landing a job as a history teacher at Highland Park in 2011.

As Davis recalls, YE -- in its earlier, more basic iteration -- had "died out" at his school. After Davis' first year at Highland Park, Vernon Birmingham approached him and his principal about bringing the course back. "They [YE] were brought in as a nonprofit to basically pitch and sell the curriculum," Davis said in an interview with HuffPost.

Birmingham saw Davis teach, and though he was not a business teacher, Birmingham told him he'd be a good candidate for the YE course.

"When I watched him in a classroom, I could see students respond to him," Birmingham said. "I immediately said Taylor's our guy -- he's energetic, he's young, students listen, he's garnered respect."

"We always say within our program ... we don't care if it's a music teacher, but if it's a teacher who can motivate students, who can move them from point A to B," Birmingham said. "They're exciting and they're passionate -- teachers who tell us that if they could teach YE all day, they would. We really look for teachers who are able to motivate and move students, move the needle."

Birmingham would become a frequent presence in Davis' classroom, keeping tabs on his lessons from the back of the room. "He would be out there quite a bit, coming into the classes," Davis said. "He was the guru of the Topeka region when I was there."

As Davis saw it, the purpose of the course was to teach teens how to become self-sufficient small business owners.

"He introduced it as giving kids real-world opportunity," Davis said of Birmingham. "YE definitely backed that up. It was a very student-centered approach that they brought me, a lot of real-world, project-based activities."

Typical lesson plans included "developing your business idea" and the "invention game."

Many students reported enjoying the course, according to Davis, and he told HuffPost that he liked teaching it. "You see students who are C or D level ... who are so bright and the traditional school system isn't working for them," Davis said, describing the program's appeal. "The idea that your actions and creativity could make you money right out of high school was a very sophisticated idea [for them] to latch onto."

In fact, Davis liked the program so much that he wants to bring it to Texas where he now works.

Before Davis taught the course for the first time in the fall of 2012, he spent an August week in a basement room at Koch Industries in Wichita, where he and about 20 other teachers learned from YE staffers and veteran instructors how to teach the class.

YE supplied Davis with a syllabus, timeline and "all the handouts that you would need," he told HuffPost. Before the school year started, he was given a thick binder of lesson plans, as well as flash drives containing quizzes and worksheets. There were also videos, PowerPoint presentations and scores of documents in Microsoft Word. Davis posted many of these resources online, offering the public a rare glimpse inside the highly structured curriculum.

Teachers participate in a Youth Entrepreneurs training session in 2012. Charles Koch's book The Science of Success is visible on the table.

As a history teacher, Davis had no background or accreditation in teaching business. "It was overwhelming," he said. So he was grateful for YE's course materials and training. "It was always an amazing support that I had, multiple people I could have contacted," he said. Birmingham helped convince the school, Davis recalled, that his teaching the class "was cool." (Similarly, Georgia's YE offshoot advertises itself to teachers by saying "CTAE [Career, Technical, and Agricultural Education] Certification NOT Required.")

YE's course materials reflect some of the initial thinking by the Koch associates charged with designing the course. In late 2009, the Koch group made a list of "common economic fallacies" that they believed should be repudiated. These included:

- Corporatism v. Free-market Capitalism

- Deregulation is what caused recession in 80s, Economic problems of today

- Rich get richer at the expense of the poor

- FDR/New Deal brought us out of the depression

- Government wealth transfer programs help the poor

- Private industry incapable of doing functions that public sector has always done

- Unions protect the employees

- People with the same job title should be paid the same amount ...

- Minimum wage, "living wage," laws are good for people/society

- Capitalist societies provide an environment for greed and materialism to flourish

- Socialist countries do just fine, people have great lives there (using this as proof that socialism works

They aimed to "inoculate" students against liberal ideas by assigning them to read passages from socialist and Marxist writers, whom they called "bad guys." These readings would then be compared to works by the "good guys" -- free-market economists like Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises.

Members of the Koch team viewed their mission as a race against the progressive left. "What is the other side doing? How is the left trying to infiltrate the educational system?" they discussed at a Jan. 12, 2010, meeting, according to notes in the Google group.

"We are operating under the assumption that high-school students do not receive an education that gives them an understanding and an affinity toward free markets," the Wu-Teach Clan stated in a project plan on Jan. 21, 2010. "Without the knowledge or affinity for free markets, students cannot appreciate the role that free markets play in laying the foundations for prosperity and freedom in society."

"We don't try to push or drive ideology," Birmingham, the YE official, told HuffPost. "From an entrepreneurial standpoint, we're big on free markets, of course. We're big on voluntary trade. We're big on property rights. All of those things align with their [the Kochs'] thoughts. Those are things that most entrepreneurs believe in."

Today, to teach its most controversial lessons, YE often relies on videos provided by the Charles Koch-chaired Institute for Humane Studies, which operates out of George Mason University in Virginia. The videos are produced and marketed under an institute arm called Learn Liberty, which offers dozens of educational videos on libertarian and conservative topics.

One such video Davis showed his students defended price-gouging. "Anti-gouging laws don't do anything to address" shortages, the video's narrator argues. Another video titled "Is There a Glass Ceiling?" asserts that the gender pay gap is a myth. Women earn around 75 cents for every dollar earned by men, it says, but not because of discrimination in the labor market. Rather, it's because of "differences in the choices that men and women make."

Other Institute for Humane Studies videos on the syllabus inform students that the cost of living isn't actually rising, that minimum wage laws harm workers and that the poor aren't "really getting poorer."

Davis also taught a series of classes based on videos by John Stossel, a lauded journalist turned conservative commentator. He showed his students Stossel's six-part series called "Greed," which posits that private companies are better at protecting the public than governments and nonprofits.

The next time his class met, Davis screened Stossel's film "Is America Number One?" in which Stossel concludes that laissez-faire economics are the key to global prosperity.

Davis said he presented these videos as simply one perspective among many. "Economics is so complex and I was never an expert on economics," he said. "Most teachers are really good at playing devil's advocate. We go on both sides of the fence. I was always challenging them to stay on both sides of everything."

He supplemented the videos with worksheets and quizzes designed to reinforce the videos' claims. "If people who make very little money have modern conveniences, are they really poor?" one worksheet asked. "True or False: International trade should be heavily regulated for the good of a country's economy," asked a quiz.

In February 2010, the Koch team who designed the course tested their libertarian curriculum with a one-semester class called "Market-Based Thinking" at the private Wichita Collegiate School. "Give the right teachers the right curriculum [and] we can influence 'thinking teenagers,'" they wrote of their plan. They aimed to measure the course's effectiveness in terms of "changing attitudes and behavior," which they acknowledged would be "hard work."

Before teaching the class, Tony Woodlief, who oversaw the Wu-Teach Clan's education project, wrote that he would "need to run by CGK for approval," referring to Charles G. Koch. In December 2009, Woodlief had good news for the group. "Charles has approved the initial draft," he wrote in an email.

Their thinking, laid out in a January project plan, was that "right-leaning private schools are more likely to have teachers and students who would be supportive of and interested in our proposed lesson plans (the low-hanging fruit)."

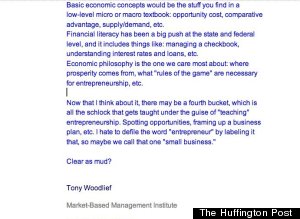

"Economic philosophy is [what] we care most about: where prosperity comes from, what 'rules of the game' are necessary for entrepreneurship, etc.," Woodlief wrote in an email. He was not interested in lessons about creating business plans or spotting opportunities to make money -- "all the schlock that gets taught under the guise of 'teaching' entrepreneurship," the things that "defile the word 'entrepreneur,'" he wrote.

Woodlief declined to comment for this article.

But the pilot program's test results showed that the private school students weren't as receptive to overtly ideological messaging as the team had hoped. What the kids did absorb were real-life examples and hands-on lessons -- the kind of approach that YE had been using since the early 1990s to teach basic business skills, like conducting market research or understanding a balance sheet.

Stephanie Linn, a member of the Wu-Teach Clan who now works at the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, told HuffPost that the associates' project had started out as little more than an exercise in nonprofit management. "The objective was for us to learn something about project management skills," she said, adding, "People weren't really interested in developing something new with us. It speaks to the absurdity of the Wu-Teach Clan name."

With what they had learned at Wichita Collegiate, however, the Koch team took the next step, according to the group's emails. Rather than create a standalone class on economic philosophy, as they had initially planned, the team proposed that they revise existing Koch-funded education programs to include more libertarian teachings. YE was a perfect fit.

"Everybody got really excited when people would find out [I was] with Youth Entrepreneurs," recalled Jon Bachura, then a Koch associate working on a different Koch Foundation project as well as a YE official. "We have access to a thousand high school-aged students a year. They always wanted to talk to me or my colleagues about, 'What are you doing?' or 'How are you doing it?'" Bachura now works for U Inc., an online training company.

At the time the Koch associates turned to it, the YE program was already in the midst of "transitioning to teach more economics," according to notes of a 2010 conversation between the Koch team and YE staff, which meant that YE "may be more willing to incorporate it into their lesson plans."

Nowadays, YE's classes have all the ideological trappings of "Market-Based Thinking" -- but instead of the politics being served straight up, it's baked into lessons about how to build a business.

The mix of practical and theoretical instruction seems to have worked well for YE. Spenser Johnson, who is currently studying criminal justice as a rising sophomore at Emporia State University in Emporia, Kansas, said he enjoyed the course and learned a lot.

"It teaches you sometimes you do have failure in business," he told HuffPost. "You have to keep going through these failures to succeed. Life's not perfect. Especially in the business world, it's hard."

While Johnson was absorbing information about free markets, the class's sponsors maintained a more subtle presence. "I don't remember a focus on Koch Industries," Johnson said. "At the events you would see the name and the pictures of them, but I don't feel like the program was focused on Koch."

In preparing to expand their course to schools beyond Wichita Collegiate, the Koch associates worried about the optics of being known as a Koch-funded group. According to the minutes of a February 2010 conference call, they concluded that marketers could "reference Koch Foundation," but "wouldn't mention it unless someone asks."

"We need to explain that we are part of a group that trains non-profit leaders and we are interested in working to improve economic education," they continued. "Basically, it is important for us to establish credibility by what we know, not who we know. We will talk about state standards, language that ties into economic education, etc. We want to steer clear from saying Koch Foundation."

As it turns out, they needn't have worried so much. When Kevin Singer, then the superintendent of Topeka Public Schools, signed a memorandum of understanding in August 2009 that expanded the YE program there, he knew exactly who was funding the course -- and it didn't bother him one bit.

Kansas is a particularly ripe state for YE to target. In addition to serving as Koch Industries' home base, the state has a public school system hungry for extra help: It's so underfunded that a few months ago the state's Supreme Court deemed school funding levels unconstitutionally low.

Singer saw YE as a welcome boon to the ailing school system -- the latest in a long string of partnerships that turned to outsiders to increase school resources for free. He came across the organization when teachers involved in an entrepreneurial club brought YE materials to his attention.

"If you can generate revenue outside of taxation, that's a positive thing," said Singer, who is now executive director of the Central Susquehanna Intermediate Unit, a Pennsylvania agency that provides budgeting, human resources, curriculum and other services to local school districts. "We couldn't have done what we did in Topeka, in giving opportunities for kids, had we not had our business partners."

Youth Entrepreneurs states that it is specifically "targeted toward at-risk youth" in predominantly poor school districts. The group agrees to pay for all of the program costs in school districts where at least 40 percent of kids are poor enough to be eligible for free and reduced-price lunches (but none of the costs in districts where fewer than 1 in 5 kids receives reduced-price lunches).

The struggling Topeka school district agreed to let YE train one new teacher a year and provide classrooms. YE would pay the teachers a stipend above their regular salary, supply them with classroom materials, arrange guest speakers and field trips, and provide students with scholarship opportunities, all at no cost to the school district.

Such public-private partnerships are a growing trend in the American education system, as corporations and interest groups come up with ever more innovative ways to market their products and ideas to students in school buildings.

In her book Born to Buy, author Juliet Schor recounts how General Mills paid Minnesota teachers $250 each to paint cereal logos on their cars and park them next to school buses. Dole offers lesson plans to elementary school teachers that are filled with positive messages about eating fruits and vegetables -- messages that also benefit the food company's bottom line.

The Society for Petroleum Engineers, together with Utah's Department of Natural Resources, once sponsored an Earth Day poster contest that asked students, "Where Would We Be Without Oil, Gas & Mining?"

"It's the same model that ... Koch's program is doing," said Faith Boninger, a researcher based at the University of Colorado, Boulder who writes about private companies in schools.

While Singer signed the memorandum of understanding before the Koch team developed YE into its current form, he said the program's connection to the Kochs did not come up once as a cause for concern during his 2008-2011 tenure. His school board voted unanimously for the program. His deputy signed another memorandum renewing the program in 2010. And in 2012, the district expanded the program to more schools and tied it to an engineering scholarship program with Westar Energy, a Kansas utility company.

"There's no way you can do these kinds of things on your own," Singer told HuffPost. "What you weigh against is, do I want to try and provide opportunities for kids that flat-out would not have them otherwise? They grew up in a very impoverished area. If you didn't have somebody [like Westar or YE] come in ... they might never, ever even know that engineering is a choice for them."

As the Kochs and their team continue to expand programs like YE, they're also gathering valuable information about how kids learn and what motivates them -- data they apply to other initiatives.

One of the fastest growing elements of YE is a program designed to keep students engaged in what is referred to across Koch-funded platforms as "the liberty movement" long after they finish the course. Launched in 2012, the YE Academy runs what it calls "economic 'think tanks' for high school students."

The academy relies on the same incentive that initially drew kids to YE: the chance to earn extra money. It rewards current students and alumni of YE for attending YE-approved lectures outside the classroom. Each event is assigned a point value, and attendees can redeem the points for scholarship money or venture capital funding.

"That’s right, the more involved you are, the more money you'll earn to put toward your business or higher education!" reads the YE Academy homepage.

YE Academy courses are also closely tailored to fit the students they hope to draw. There's an Urban Economics Academy, where students take bimonthly online economics classes on topics such as "relocation of businesses, suburban flight, minimum wage laws, constitutional rights, Affordable Health Care Act, and many more!" A Rural Economics Academy tackles farming issues and is "open to anyone who has familiarity with rural landscapes and concepts." A Migrant Economics Academy explores "the economics of immigration."

Luis Garcia, whose mother brought him to the U.S. from Mexico in search of a better education, took part in the Migrant Economics Academy as a senior in high school, one year after he took the YE class. He told HuffPost that he earned $2,000 in scholarship money from all the YE Academy points he racked up. He put the money toward his studies at the University of Southern California, where he is currently a rising sophomore.

"I didn't get capital for a business, but the capital that I did receive ... I chose to invest it in education," he said. "It was a significant amount as to what my parents had to pay."

The success of the YE Academy -- over 500 students took part in the first year -- suggests that offering tangible incentives to young people in exchange for consuming ideological offerings could be a winning formula, better than the Wichita Collegiate class at least. It's certainly one the Kochs were quick to replicate. At the Institute for Humane Studies, the Liberty Rising program begun earlier this year offers students "swag" in exchange for watching videos, the same ones Taylor Davis showed in his classroom.

The Liberty Rising marketing targets teens and young adults. "Who doesn't like freedom -- and free stuff? Rack up points and score sweet goodies like T-shirts, posters, and games, including the highly coveted 'Freer Pong,'" the website says. In order to view the swag, users must provide a wealth of information to the Institute for Humane Studies.

Youth Entrepreneurs is just one piece of the Kochs' slow creep into America's schools. The larger Koch effort pushes forward with think tanks, university programs and teacher seminars as well.

But with YE, the Koch pipeline for creating a new generation of liberty advancers now starts early: A student can take the YE course in high school, participate in the YE Academy to earn scholarship money and then use that money to pay for a degree from a Koch-funded university. So it isn't just a relatively small but growing high school program offered in Kansas and Missouri. It's part of a larger mission.

"Everybody that's interested in liberty-minded higher education and beyond is really excited about Youth Entrepreneurs," Jon Bachura told HuffPost, adding, "It's all playing in the sandbox to see what things, what activities answer that question: What creates the liberty mindset?"

"All the power is yours," Tony Woodlief imagined teachers telling their students. "What will you do to make your country wealthy? How will you produce entrepreneurs and get them working on the things that matter?"

Editor's Note: The publicly accessible archive for Taylor Davis' curriculum was taken down following the publication of this article; links to the site have been replaced with those for an archive of that material.